|

|

|

|

|

|

Classic Bikes

Custom Bikes

Individual

Racing Bikes AJP

AJS

Aprilia

Ariel

Avinton / Wakan

Bajaj

Benelli

Beta

Bimota

BMW

Brough Superior

BRP Cam-Am

BSA

Buell / EBR

Bultaco

Cagiva

Campagna

CCM

CF Moto

Combat Motors

Derbi

Deus

Ducati

Excelsior

GASGAS

Ghezzi Brian

Gilera

GIMA

Harley Davidson

Hero

Highland

Honda

Horex

Husaberg

Husqvarna

Hyosung

Indian

Jawa

Kawasaki

KTM

KYMCO

Laverda

Lazareth

Magni

Maico

Mash

Matchless

Mondial

Moto Guzzi

Moto Morini

MV Agusta

MZ / MuZ

NCR

Norton

NSU

Paton

Peugeot

Piaggio

Revival Cycles

Roland Sands

Royal Enfield

Sachs

Sherco

Sunbeam

Suzuki

SWM

SYM

Triumph

TVS

Ural

Velocette

Vespa

Victory

Vincent

VOR

Voxan

Vyrus

Walt Siegl

Walz

Wrenchmonkees

Wunderlich

XTR / Radical

Yamaha

Zero

Video

Technical

Complete Manufacturer List

|

Moto Guzzi 850 Le Mans III Mark

|

| . |

|

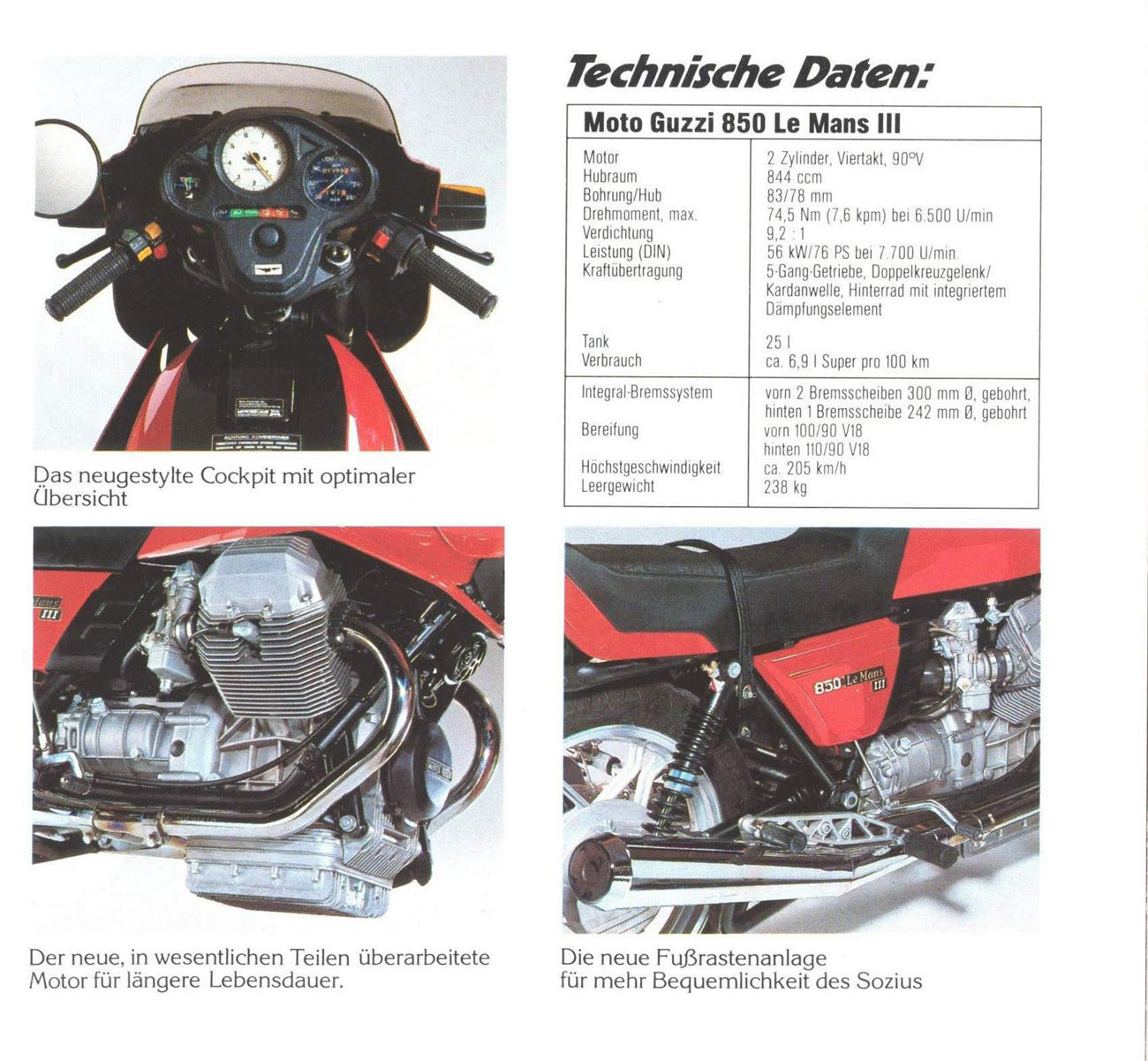

Make Model |

Moto Guzzi 850 Le Mans Mark III |

|

Year |

1981 - 82 |

|

Engine |

Four stroke, 90° V twin, longitudinally mounted, OHV pushrod, 2 valves per cylinder |

|

Capacity |

844 cc / 51.5 cu-in |

| Bore x Stroke | 83 x 78 mm |

| Cooling System | Air cooled |

| Compression Ratio | 9.8:1 |

| Lubrication | Pressure pump |

|

Induction |

2x 36mm Dell'Orto carburetors with accelerator pump, with air filtering and inlet silencer |

|

Ignition |

Battery and coil |

| Starting | Electric |

|

Max Power |

76 hp / 56 kW @ 7700 rpm |

|

Max Torque |

74.5 Nm / 54.9 lb-ft @ 6200 rpm |

| Clutch | Dry with double disc |

|

Transmission |

5 Speed |

| Final Drive | Shaft |

| Frame | Duplex cradle, disasemblable |

|

Front Suspension |

35mm Telescopic air assisted forks |

| Front Wheel Travel | 140 mm / 5.5 in |

|

Rear Suspension |

Dual charged shocks, spring preload adjustable |

| Rear Wheel Travel | 94 mm / 3.7 in |

| Wheels | Light alloy casting |

|

Front Brakes |

2x 300mm discs 2 piston calipers |

|

Rear Brakes |

Single 242mm disc 2 piston caliper |

|

Front Tyre |

100/90 V18 |

|

Rear Tyre |

110/90 V18 |

|

Dry Weight |

206 kg / 454 lbs |

|

Fuel Capacity |

25 Litres / 6.0 US gal |

|

Consumption Average |

43.5 mpg |

|

Standing ¼ Mile |

12.6 sec / 106.3 mph |

|

Top Speed |

132 mph |

| Road Test | Ducati 900SS vs Le Mans III |

| . |

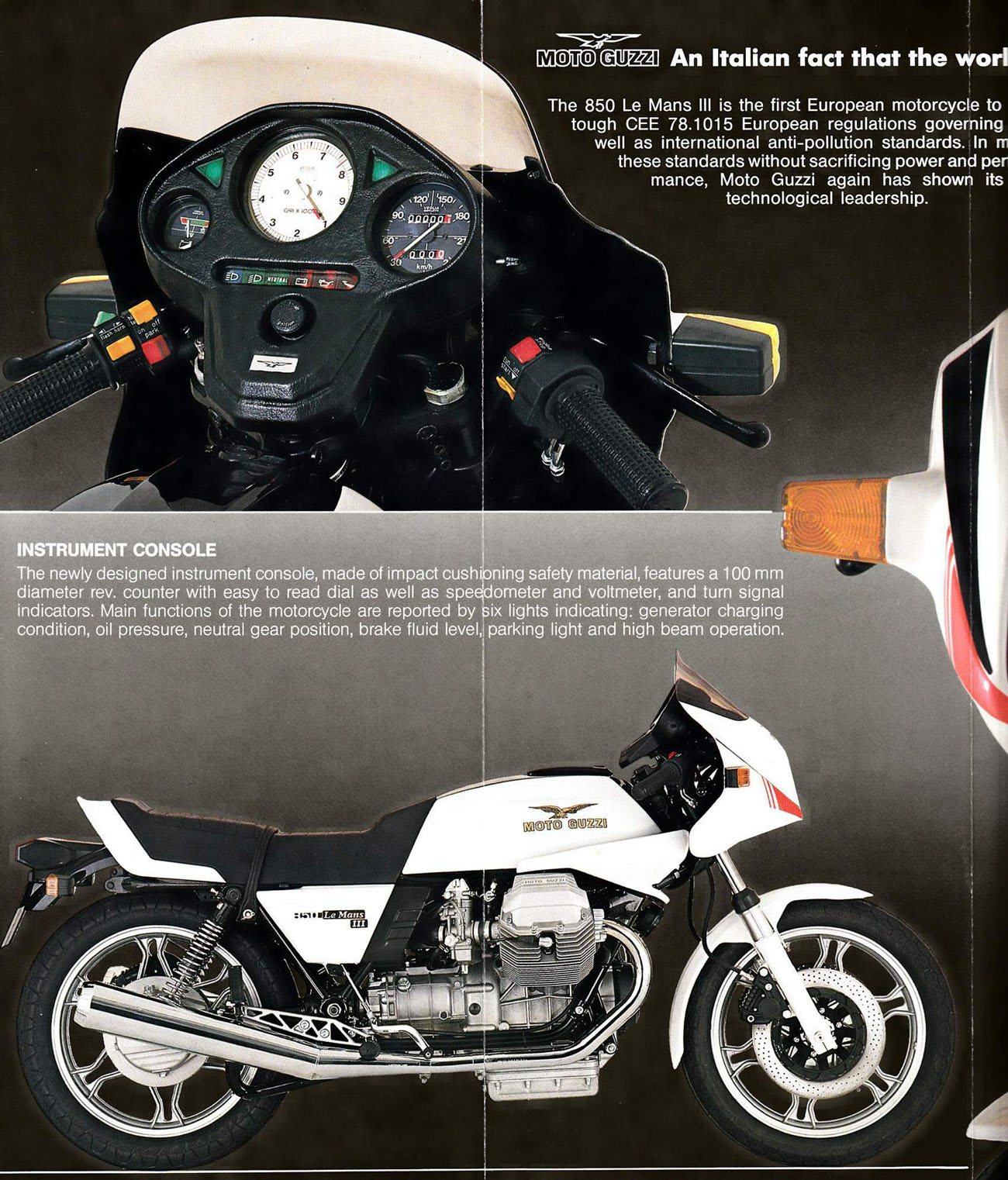

Here's the late-breaking good news from Italy: the 850 Le Mans under Mark III labeling, is back. Several years ago the big-carburetor, high-compression, real-sting 850 fell victim to U.S. clean air regulations; in the interim, Le Mans units bound for America got the standard 949cc engine, a nice enough droner which felt about as vicious as a June moth. This year, though, we welcome back the smaller, more intense 850 Le Mans, now certified for U.S. atmospheres.

More good news comes in the form of a multitude of changes, made in European versions over the last couple of years and finally available in domestic models; a new distributor: Benelli North America; and reduced prices: the CX100 last year cost $5498, the Le Mans III is $4518.

While the 850 Le Mans was missing from the U.S. sport-bike landscape, the scenery changed considerably. For example, since 1978 Honda twice re-invented its sport 750, as did Suzuki. Currently, the Honda Interceptor/Suzuki GS750ES/Kawasaki GPz750 are the most European, least "traditional" Japanese motorcycles ever. '

Into this radically altered scene comes the Le Mans III, inviolate. Italians refuse to be shaken by the way the Japanese do things. A small example? Moto Guzzi cares little whether anyone else in the world puts their crankcase webbing outside; they believe it should be outside, and that's where it is. Anyone coming off a Japanese motorcycle will think the Le Mans a bit strange, foreign, idiosyncratic. You name it, it's different: switches, seating position, handling, the quality of power. Guzzis, and especially this one, delight people who thrive on the unique.

For 1983, the Guzzi lineup includes the Le Mans 850; the California II (G5), with a 949cc angular-fin engine; and the SP model, with its round-cylinder 949cc boomer. All three machines meet tightening worldwide emission standards. Yes, European countries have standards too, some quite strict. One mandates 83 dB[A] noise levels, and this explains the new intake silencer/air filter and new exhaust system on this year's Mark III.

The '83 Le Mans has 44 individual changes compared to the Mark II, and even more matched against the CX100. Externally, angular cooling fins and new bodywork identify the new model, but the real changes hide inside.

Though our cover bike was a Mark III in standard trim, our test unit, the personal bike of Jim Woods, a Glendale-based Moto Guzzi dealer, had some cosmetic changes: Kal-Gard-painted wheels and final-drive unit; polished float bowls and muffler brackets; non-resistor-type spark plug caps. Then there were the removals: the fairing's reflective tape and the sidestand. A quartz halogen headlight bulb replaced the standard tungsten unit, and a bar-end rearview mirror replaced the stock clutch-lever-mounted unit.

Angular cylinder and head finning increases cooling area slightly, but internally the cylinders have new hard-plated bores. Moto Guzzi developed and patented a new process called Nigusil, which, according to Guzzi spokesmen, differs from other hard-surface treatments. The Guzzi process is galvanic, electrolytically combining solid silicon carbide particles uniformly in a nickel deposit. This process, pioneered on the V35 and V50 Moto Guzzis, improved wear resistance over the old chrome bores and reduced oil consumption. Now all Guzzis have Nigusil cylinders.

The 850 Le Mans' port sizes, valves and carburetors differ from the CX100's. At 44mm the 850's intake valves are four millimeters larger, and at 37mm exhaust valves are 1.5mm bigger in diameter. Included valve angle is relatively shallow at 70 degrees. The intake stem necks down beneath the guide and the valves are highly polished. Although the Le Mans' port shapes are basically similar to the standard Guzzis', they are much larger and, like the valves, their surfaces are more smoothly finished.

The Le Mans III camshaft, chain-driven from the crank's nose, uses more radical timing than that of the old CX100, yet the numbers are mild by sport-bike standards. Duration for both intake and exhaust is 252 degrees, and overlap is 40 degrees.

The 36mm Dell'Orto pumper carburetors are six millimeters larger than the 1000's units, which belonged to the low-performance square-slide Dell'Orto series. A conventional diaphragm-type pump squirts fuel from a nozzle into the airstream; this differs from the CX100's spring-and-plunger affair, which dribbled a few drops through the carb's main nozzle at the venturi's floor. The "real" 36mm pumpers atomize fuel more effectively. They appeared on the first Le Mans in the U.S. in the late 1970s, but emission standards forced their replacement with square-slide carbs, holdovers from the 1960s.

Our Le Mans always started quickly with minimal choking. The carbs' big throats make the power a little doggy at low speeds and revvy at high speeds. The bike pulls willingly from near-idle revs, and the progressive power pulls enthusiastically from 6000 rpm to redline. Our 850 averaged 49.6 mpg on the open highway, giving a 250-mile cruising range on the main supply. The engine was designed for leaded fuels 98/100 octane (RM) is the recommended minimum. The original Le Mans had small unfiltered stacks on each carb, while the CX100 used a circular filter in an airbox connected to both carbs. The new setup uses a flat filter buried among frame tubes between the carbs. Crankcase and cylinder head fumes vent through the top main tube before entering burns both cleaner and quieter than the old, and very little intake-tract gurgling rises up to the rider.

Downstairs the powerplant remains unchanged. The inside-out case contains the same one-piece forged crankshaft and rods as before. The crank rides on plain bearings supported by large aluminum carriers which bolt into the one-piece case. Twin connecting rods ride side-by-side on a single throw, causing only a slight rocking couple. The pork-chop-style crank supplies some flywheel effect; however, the heavy clutch flywheel contains most of the rotating mass.

Driveline lash is minimal. Power runs through only a few gears, and all of these are helical-cut. Primary gears pass the power directly to the gearbox; the drive shaft turns directly from the gearbox to the final-drive unit. What lash can be detected arises from the rubber cushion in the rear hub and a spring-ramp shock absorber in the transmission. Shifting feels notchy at first, and clunky until the rider acquaints himself with the clutch and shift pedal engagement arcs. A full, forceful throw from second to third is the only way to avoid a false neutral. We've been told this is common but not universal among Guzzis.

While the chrome-plated exhaust system no longer has a forward crossover pipe, the rear crossover behind the engine remains. New seamless mufflers quell more escaping exhaust noise than the old seamed silencers did. Our test Le Mans runs quieter, quicker and cleaner than former types. The only unusual mechanical noise is a rattling when the clutch disengages.

The new fairing, smaller than the CX's, protects the rider's lower torso and hands without turbulence, and blends nicely with the slightly longer and-larger-capacity (6.6-gallon) gas tank. The small frame-mount spoiler augmenting the fairing resembles the '82 bike's, but lacks the extended lower section. Because all Guzzi airfoils have their shape determined in the company's wind tunnel, the Le Mans remains relatively insensitive to cross-winds, even at high speeds. Incidentally, a slightly longer swing arm stretches the wheelbase 0.5 inch over the CX100, to 59 inches.

Air-charged suspension now supports the Le Mans. The rear springs have five-position preload adjustment, but damping rates can't be varied. The manual calls for 42 psi front and 56 psi rear. Set up this way, the springing is too stiff; under hard acceleration the drive-shaft's torque effect locks the rear end full-rigid. Experimenting led staffers to lower pressures, usually around 10-15 psi front and 20-30 psi rear. With this springing, the Le Mans' only major shortcoming is occasional bottoming at the rear on large, nasty bumps, which it does even at full pressure. Damping, front and rear, suits the springing well when the air pressure is set below recommended levels, but the soft approach still has some drawbacks. The rear end suffers some up/down porpoising during on/off throttling. When the rider chops the throttle mid-corner, the bike sags, eroding ground clearance. Easing off the throttle in corners can set up a mild fork oscillation, which disappears (or never appears at all) if the rider keeps the engine under throttle.

The Pirelli tires are very good indeed: they track straight and stick well during hard cornering, and they let the rider know when breakaway is approaching. However, they also wear quickly. According to Woods, the OEM 100/90 MT29 front tire can wear out under severe use in about two thousand miles, though using a 4.10 MT28 on the front will double tire life for hard riders. The MT28, intended for use on the rear wheel, hasn't a rib-pattern. The Le Mans' steering was extremely slow and heavy with the MT28, and the Mark III felt reluctant to change direction deftly. Stability was excellent; the bike stayed well planted and the front tire stuck securely. During hard cornering, the rear tire would creep—at the limit of adhesion—after the footrests grounded firmly. Later we installed the OEM tire with its smaller cross-section and ribbed tread pattern. The Le Mans steered lighter and leaned into corners much more quickly. Most staffers, save our hard-core chargers who crowd the limits, preferred the MT29. The extremists thought the bike lost its nailed-down feeling with the 29, that the front end seemed less secure and planted, before the rear tire began to creep.

After grounding a few times', the footrest rubbers loosened on their pegs, then began spinning on their shafts whenever they hit ground. On the left the centerstand grounds next; we touched nothing on the right except the brake pedal.

Moto Guzzi's Integral Braking system has the rear brake pedal operate both the left front disc and the rear brake, while the front brake lever independently operates the other front disc. Integral systems have not impressed Cycle's testers until now; other systems have lacked progressive feedback, outright stopping power, or both. The Le Mans' connected system stops the bike quickly and controllably, partly due to the excellent Brembo calipers and discs. Using the rear pedal alone stops the bike straight and sure; increased pedal pressure causes solid, progressive stopping force. Using the front brake lever in addition to the pedal bulges the rider's eyeballs right against his faceshield. The front lever on our test machine was somewhat spongy under hard use, giving disproportionate lever travel. Furthermore, the brake lever engages at some distance from the grip, so throttle manipulation is difficult during downshifting. Despite this, braking is impressive.

A bright, clearly marked four-inch tachometer dominates the instrument console. Easy-to-see turn signal indicators flank the tach, a location we liked. The panel's asymmetrical arrangement may seem odd, yet the dial faces and warning lights are easily read and plainly labeled. The many electrical switches might initially baffle even a space shuttle technician; with time their operation becomes natural.

The Le Mans' seating position throws the rider's weight onto the handlebars, straining arms and wrists, especially during hard braking. Cylinder heads intrude on the rider's knee space, and sliding rearward to avoid this stretches his torso even more. To work the bike hard, a rider must slide forward, and to do this he needs to splay his legs to avoid the heads. If he does splay his legs, however, he can't grip the tank to keep from sliding forward even further. The seat is typically full-sport Italian: board-hard. Its relative narrowness went pretty much unnoticed because of the saddle's firmness and its ability to transmit bike movement straight into the rider. A bumpy road will have the rider looking for a rest stop inside an hour.

Understand, the Le Mans is its own kind of motorcycle, distinct and unique. Someone coming off a Japanese bike will have to adapt to the machine; the Moto Guzzi certainly isn't going to adapt to the rider. Consider the gearbox. The shift throw is long and the rider must use every millimeter of it to get the right gear. Likewise, the switches are at first confusing; the steering feels awkWard; the torque reaction of the longitudinally mounted engine feels strange; and the integrated brake system strikes some as ineffective.

A Japanese manufacturer would consider the Moto Guzzi Le Mans a disaster—the Japanese must build each of their motorcycles for wide audiences. Even the most notorious ergonomic catastrophes of the Japanese cruiser genre must necessarily have a broader appeal than the Le Mans. The Japanese have sold more cruisers in the last six months than Moto Guzzi will sell Le Mans in the next 15 years. Those tiny numbers explain precisely why Moto Guzzi designers can get away with building motorcycles their way. The Le Mans just isn't made for everyone.

It dares to be what Italian designers believe a sport motorcycle should be, Marketing Department be hanged. If you don't like it, don't worry they don't care. They figure a handful of cognoscenti will always be around to buy an equally small number of Moto Guzzis, so if the Le Mans doesn't suit you, don't bother waiting around for Guzzi engineers to make a bike that will. That'll be the day.

Source Cycle 1983

|

Any corrections or more information on these motorcycles will be kindly appreciated. |